Western Art History – Ancient Greek Art

This series aims to break down and present western art history into bite-sized chunks with the hope to develop a stronger visual literacy and a bucketload of inspiration.

Let’s consider the idea that no artwork lives in a void and that knowing what came before can lead to innovation by adding upon or breaking away and in the process allow us to pay our respects to those paths forged before us.

Wiki is my friend for this series and the roadmap for the series is via this linear progression.

Today we’re exploring the art in ancient Greece – you can track back the rest of the series here!

ANCIENT GREEK ART

Quick heads up!

Large quantities of ancient Greek pottery and sculpture remain but missing almost entirely are paintings and art in other perishable materials. The stone shell of a number of temples survived but little of the decoration. What can be surmised about Greek painting, is drawn from parallels in vase painting, late Greco-Roman copies in mosaic and fresco, some examples of painting in the Greek tradition, and within the ancient literature. (source)

To get a grasp on ancient Greek Art, this entry will be broken down into when, what, who, how, and why.

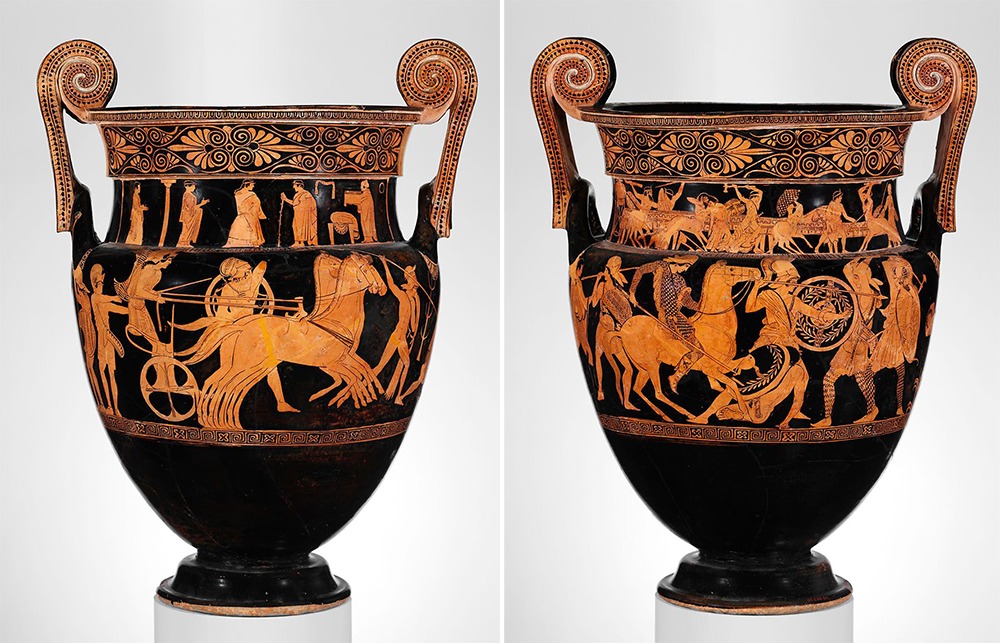

Terracotta volute-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water) ca. 450 BCE (source)

Despite no sharp transitions from one period to another (art developed at different speeds, in different parts of the Greek world and by different artists) the art of ancient Greece is typically and stylistically divided into four periods: the Geometric, Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic (source).

Geometric (900-700BC)

Archaic (700 – 480BC)

Classical (480-323 BC)

Hellenistic (323-31BC)

(source)

PAINTING

There is a considerable body of literature on Greek painting and painters despite none of the work mentioned having survived. In contrast, there are no mentions of vase painting in literature but over 100,000 surviving examples, giving many individual painters a respectable surviving oeuvre.

Early painting seems to have developed along similar lines to vase painting, heavily reliant on outline and flat areas of colour, but then flowered and developed at the time that vase painting went into decline.

The most common and respected form of art, according to authors like Pliny or Pausanias, were panel paintings (individual, portable paintings on wood boards) commonly depicting portraits and still-lifes. (source)

Symposium scene in the Tomb of the Diver at Paestum, c. 480 BC (source)

SCULPTURE

The idealization of white marble is an aesthetic born of a mistake. Much of the sculpture of ancient Greece was polychromatic (painted colourfully) and over the millennia, the paint wore off through exposure to the elements. (source 1/2)

Bronze, valued for its tensile strength and lustrous beauty, became the preferred medium for freestanding statuary, although very few originals survived – what we know of comes primarily from ancient literature and later Roman copies in marble. (source)

The surviving ancient Greek sculptures were mostly made of two types of material; stone (especially marble or other high-quality limestones) carved by hand with metal tools. Stone sculptures could be free-standing fully carved in the round (statues), or only partially carved reliefs attached to a background plaque, such as architectural friezes or grave stelai. Friezes were incorporated into temple design and featured mythological and historical scenes and occasionally animals. The Parthenon frieze includes Gods, musicians, soldiers, weavers, elders, and heroes. (source)

A color reconstruction of the sculpture thought to be Paris, the Trojan prince who killed Achilles (source)

WHAT MADE ANCIENT GREEK ART UNIQUE?

Artistic schools, for the first time, were established as institutions of learning. During the 4th century BC, the city (Sicyon/Sikyon) reached its zenith as a center of art and attracted famous artists from all over Greece to their school, including the celebrated Apelles and Pausias.

Ancient Greek sculptors pathed the way for realistic sculpture and inspired the Italian renaissance in the 14th century, whilst ancient Greece’s societal emphasis on the arts remains influential to this day. (source 1/2)

Below, we’ll dive into what made each period within ancient Greek art unique.

GEOMETRIC PERIOD

The Geometric period saw pottery decorated with bands of lines and patterns. Images of people, animals, and chariots appeared but were painted using geometric shapes that resulted in unrealistic and blocky forms. (source)

Terracotta neck-amphora 4th quarter of the 8th century BCE using black-figure pottery technique (source)

ARCHAIC PERIOD

During the Archaic period, Greeks began to carve large freestanding sculptures of human subjects from stone – male nude statues called kouros, and female clothed statues called kore. The rigid posture of these statues often with one foot forward and hands by their sides illustrates the Ancient Egyptian influences and the contact between the two cultures as well as influences from the Near East. After 575 BC these statues wore the archaic smile

Black-figure pottery (the subject painted black, with details etched away) from the Attic region of Greece continued on from the geometric period and increased in popularity. Diverse scenes displayed (daily life, warfare, and mythology) that were more narrative in depiction than what had been seen in the geometric period. (source 1/2)

Peplos Kore, c. 530 B.C.E. and Anavysos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.E. displaying the archaic smile (source)

CLASSICAL PERIOD

The Classical period, often defined by the Greek defeat of the Persians in 479 BCE, ushered in what is now known as the Golden Age of Greece. During this period Greek art was characterised by proportional beauty, physical perfection, and idealisation.

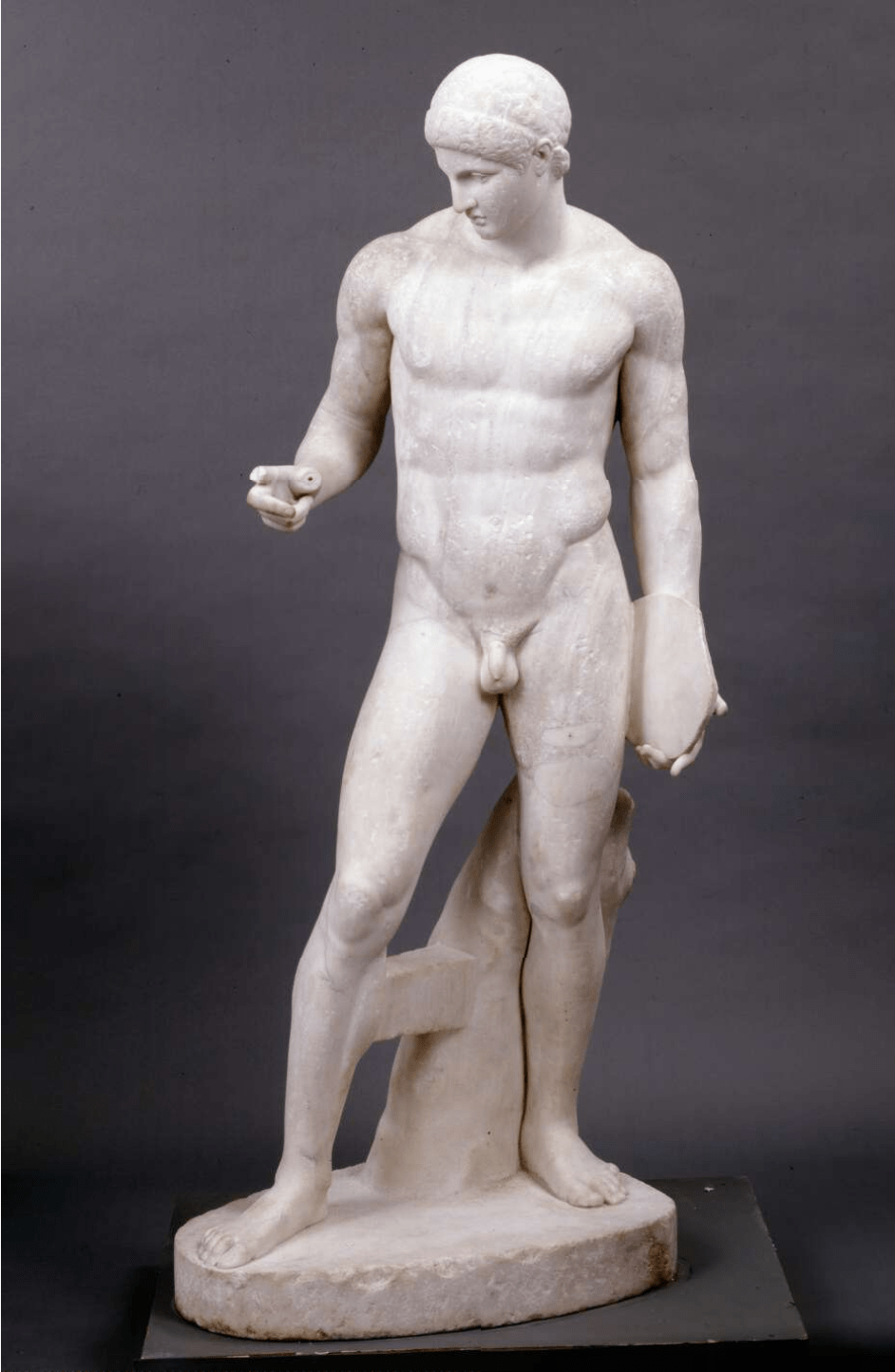

The introduction of the contrapposto, a fluid stance with twisted hips and bent knee, appeared during the classical period when poses became more fluid, dynamic, and naturalistic than what had appeared during the Archaic period.

Canonised human proportions were also seen where the ‘ideal’ human, was 7 heads tall, as defined by sculptor. In the late classical period, Praxiteles canonised the 8-head figure with an added s-curve.

The black figure painting of the Archaic period was replaced by the red-figure painting (background painted black, fine details of subjects painted on top of natural red clay) which allowed for greater detail through the use of brushes over engraving.

White marble statue of athlete in contrapposto stance (source)

HELLENISTIC PERIOD

The final transition to the Hellenistic period occurred following the death of Alexander the Great, who famously spread Greek culture into the lands of his far-reaching conquest. The Hellenistic era spanned 300 years and was marked by inventions, globalisation, and cultural connection via a shared language and standardised schooling. A rich society with famous patrons of the arts who commissioned public projects of sculpture as well as private luxuries to demonstrate their money and social standing.

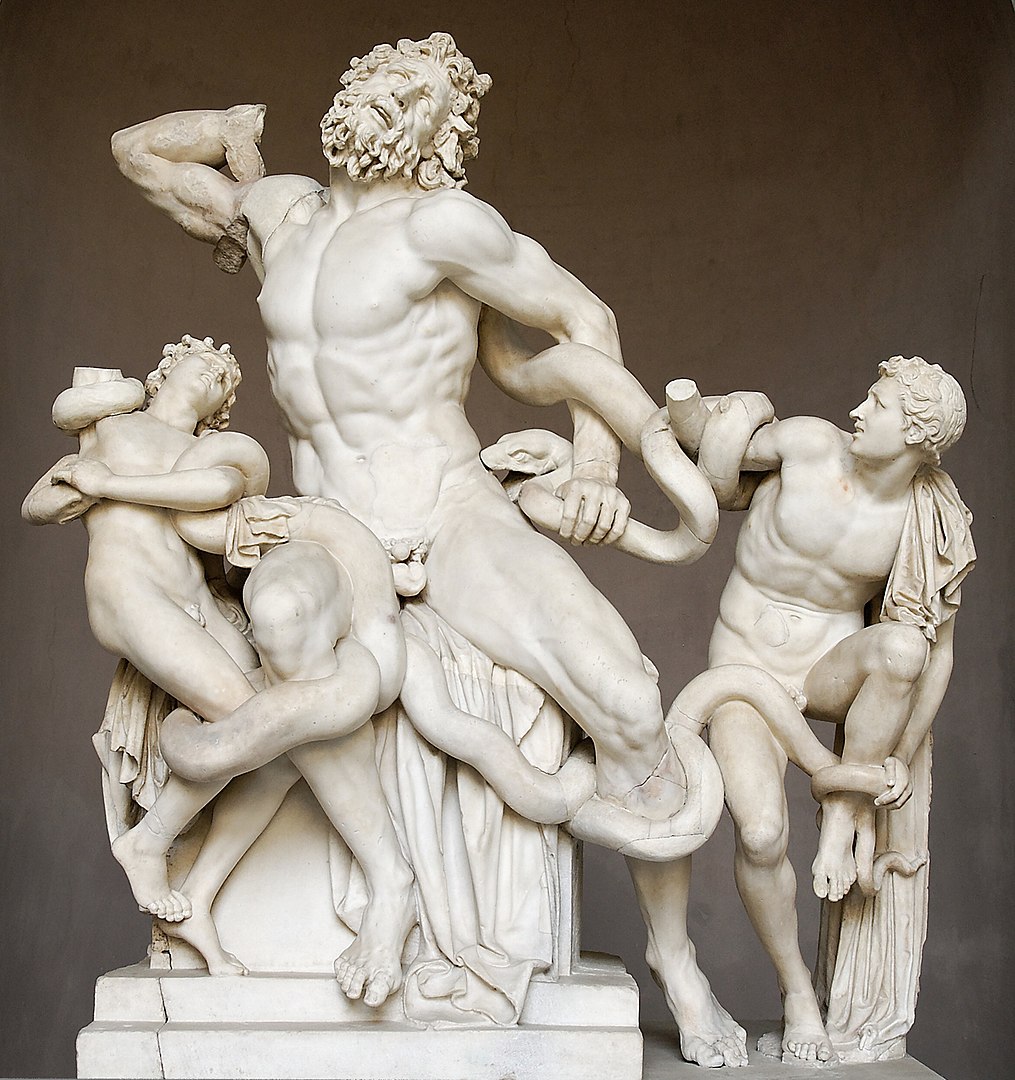

Art grew increasingly lifelike and expressive throughout this period, with an emphasis on conveying extremes of expression and personality. Artists no longer felt obligated to show individuals as standards of beauty or bodily perfection but rather to portray accurate representations of people and nature.

A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to this period, including Laocoön and His Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace.

By the end of the Hellenistic period, technical developments included modelling to indicate contours in forms, foreshortening, three-dimensional viewpoint, interior and landscape backgrounds, and the use of changing colours to suggest distance in landscapes and light and shadows to convey form. It was also the first time artists used, Trompe-l’œi where art on a two-dimensional surface creates an optical illusion of three-dimensional space.

Laocoön and his sons (source)

During his reign, Alexander cultivated the arts as no patron had done before him. Among his retinue of artists was the court sculptor Lysippos, arguably one of the most important artists of the fourth century B.C.

The most famous works of the Classical period were the colossal Statue of Zeus at Olympia and the gold and ivory (chryselephantine) Statue of Athena Parthenos at the Parthenon. Both were executed by Phidias or under his direction, and are now lost, although smaller copies (in other materials) and descriptions of both still exist.

We know the names of many famous painters, mainly of the Classical and Hellenistic periods, from literature. The most famous of all ancient Greek painters was Apelles of Kos, whom Pliny the Elder lauded as having “surpassed all the other painters who either preceded or succeeded him.”

Polykleitos of Argos was particularly famous for formulating the 7 head system of proportions. Later Athenian sculptor Praxiteles, canonised the 8 head figure with an added s-curve. Praxiteles most celebrated work, Aphrodite of Cnidus, a female goddess shown naked – was a bold innovation at the time. According to Roman author Pliny the Elder, when Praxiteles was asked which of his statues he valued most highly, he replied, “Those to which Nicias [a famous Greek painter] has put his hand’.

Ancient Greek painter Pausias is thought to have invented the encaustic painting method and introduced the custom of painting the ceilings of houses. He was proud of being able to finish a picture in just 24 hours and was noted for his ability to use foreshortening.

Sosos of Pergamon, a prominent artist in the 2nd century BC, had an interest in optical illusion. The Unswept Floor in the Vatican Museum, which depicts the leftovers of a meal, and the Dove Basin at the Capitoline Museum (known thanks to a reproduction discovered) both utilising 3-d techniques (Trompe-l’œi).

Greek pottery was frequently signed, sometimes by the potter or the master of the pottery, but only occasionally by the painter. Hundreds of painters are, however, identifiable by their artistic personalities: where their signatures have not survived they are named for their subject choices, such as the Achilles Painter, by the potter they worked for, such as the late Archaic Kleophrades Painter, or even by their modern locations, such as the late Archaic Berlin Painter. Other vase painters such as Douris, Makron, and Kleophrades exhibited exquisitely rendered details.

Unswept Floor, Roman copy of the mosaic by Sosus of Pergamon (source)

The secco and fresco methods were used in wall art during the Hellenistic period. The fresco technique required layers of lime-rich plaster to be applied to the surface before they could be decorated, whilst the secco method, employed gum arabic and egg tempera to create features on marble or other stone. Both techniques made use of locally available materials, manufactured artificial pigments, and organic materials as colorants.

The evolution of mosaic artwork during the Hellenistic Era started with pebble mosaics, best depicted in the 5th century BC at the site of Olynthos. Pebble mosaics were created by arranging tiny black and white pebbles of varying sizes in a rectangular or circular panel to depict images from mythology.

The mosaics at the site of Pella, during the 4th century BC, show the usage of stones that have been tinted in a wider spectrum of hues and tones and demonstrate the use of lead wire and terracotta to generate more defined curves and features.

From the third century BC, increased usage of precisely cut pebbles, broken stones, glass, and baked ceramic, known as tesserae, are seen. (source)

Lion hunt. Mosaic from Pella (ancient Macedonia), late 4th century BC, depicting Alexander the Great and Craterus (source)

The Greeks decided very early on that the human form was the most important subject for artistic endeavour. Seeing their gods as having human form, there was little distinction between the sacred and the secular in art—the human body was both secular and sacred. A male nude of Heracles had only slight differences in treatment to one of that year’s Olympic boxing champion. The Greeks did not produce monumental sculpture merely for artistic display, statues were commissioned either by aristocratic individuals or by the state, and used for public memorials, as offerings to temples, oracles, and sanctuaries (as is frequently shown by inscriptions on the statues), or as markers for graves. (source)

Marble grave stele with a family group ca. 360 BCE (source)

I hope you’ve enjoyed this journey into Ancient Greek Art!

–

Want to see what else I do? Come peek over on my insta or grab a freebie when you sign up to my newsletter below 🙂 🙂