Western Art History – Medieval Art

This series aims to break down and present western art history into bite-sized chunks with the hope to develop a stronger visual literacy and a bucketload of inspiration.

Let’s consider the idea that no artwork lives in a void and that knowing what came before can lead to innovation by adding upon or breaking away and in the process allow us to pay our respects to those paths forged before us.

Wiki is my friend for this series and the roadmap for the series is via this linear progression.

Today we’re exploring Medieval art – you can track back the rest of the series here!

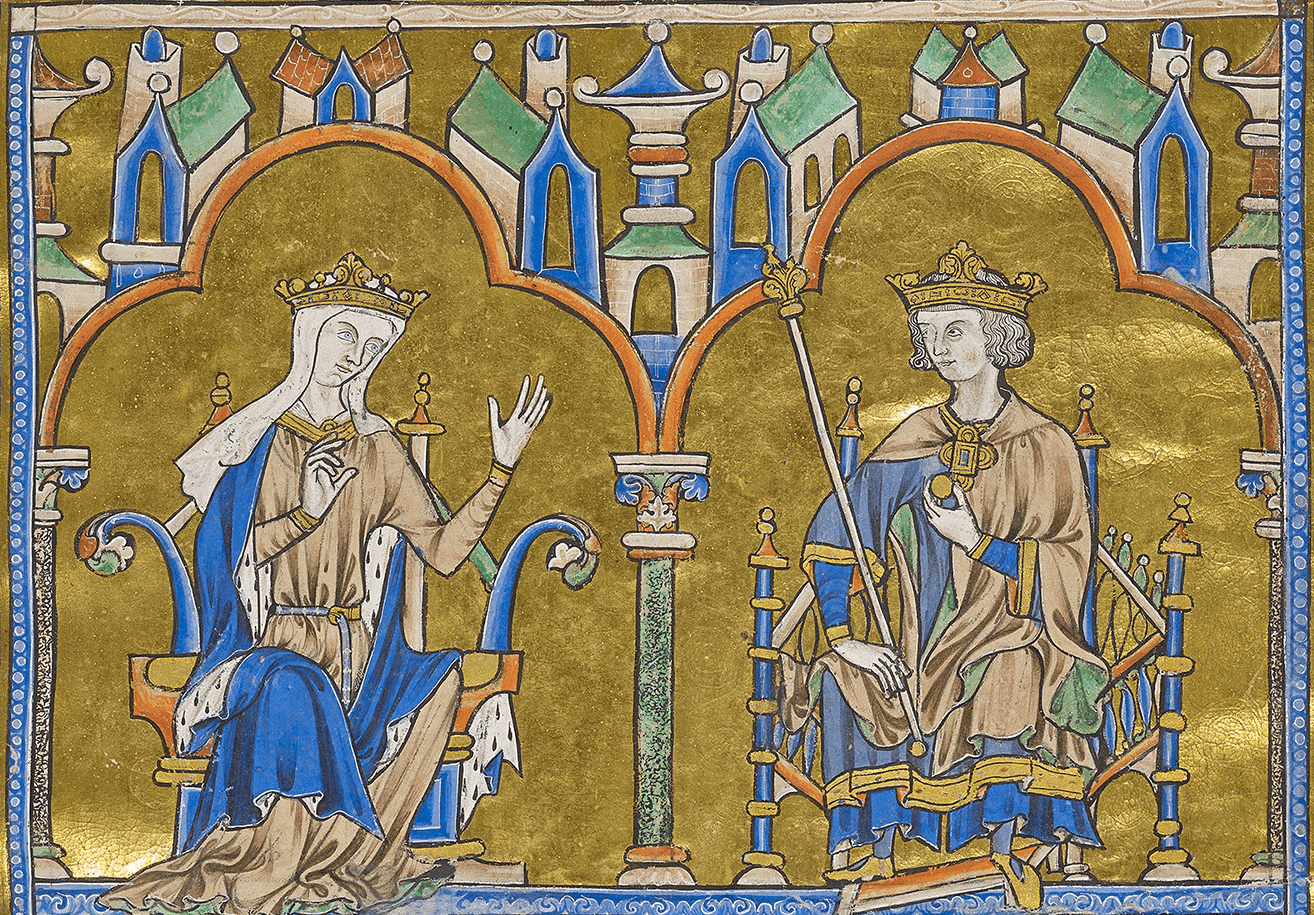

Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France (detail), Bible of Saint Louis (Moralized Bible), c. 1227–34, ink, tempera, and gold leaf on vellum (source)

Medieval ART

Medieval art refers to a period also known as the Middle Ages, which roughly spanned from the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 AD to the early stages of the Renaissance in the 14th century. The break-up of the Western Roman Empire was accompanied by wars/invasions across Europe alongside major societal, cultural, and artistic changes.

Medieval art was a fusion of three important traditions:

/Greco-Roman heritage

/traditions of various people living or newly settled in Northern Europe

/relatively new Christian faith.

Art produced during the middle ages occurred across a vast scope of place and time (ten centuries) and included a wide range of genres and mediums. This series will focus on art produced in the west (Northern Europe) with mentions made of eastern influences, especially Byzantine art (Eastern Mediterranean).

Reliquary Shrine Attributed to Jean de Touyl, France, ca. 1325–50 CE (source)

To get a grasp on Medieval Art, this entry will be broken down into the what & when with a deeper dive into each different period. This entry is fairly heavy on history but I believe the context of the time is important when jumping from Roman Art to understanding the art produced during the Middle Ages.

Angels Swinging Censers, made in Troyes ca. 1170 CE (source)

WHAT

Medieval art was produced in many media but its sculpture, illuminated manuscripts, stained glass, metalwork, and mosaics have had a higher survival rate compared to other media such as fresco wall-paintings, work in precious metals, or textiles such as tapestry. A prominent feature of the period was the use of valuable materials (such as gold) displayed within church artworks, personal jewelry, mosaic backgrounds, and gold leaf in manuscripts.

Manuscript Leaf with the Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, from a Laudario 1340 CE ITALY (source)

illuminated manuscripts

Illuminated manuscripts (texts of a religious, devotional, or theological nature) were accompanied by decoration in the form of illustrations, initials, and marks in the borders (marginalia). A manuscript was only considered to be illuminated if the text was decorated in either gold or silver. Resilient animal skin pages, protected by stout wooden boards have allowed illuminated books to last almost indefinitely, alongside their decorations, usually found in a remarkably good state of preservation.

Plaque with Censing Angels ca. 1170–80 CE FRANCE (source)

WHAT MADE MEDIEVAL ART UNIQUE?

The Christian artist had a new and uncharted opportunity of creating a complete iconography of the visual side of religion.

Christian images were in use everywhere: both as icons (functioning as focal points of worship) and as symbolic and narrative compositions, proclaiming the mysteries of the faith. For the newly converted (and largely illiterate medieval society), such imagery would have been one of Christianity’s most arresting and tangible features.

The gates of heaven and the mouth of hell (detail), Last Judgment tympanum, Church of Sainte Foy, France, Conques, c. 1050–1130 (source)

The Middle Ages neither begins nor ends neatly at any particular date. Art historians generally classify Western Medieval Art into the following periods (with approx. time frames)

Early Medieval Art: 400 – 1000 CE

Romanesque Art: 1000 – 1200 CE

Gothic Art: 1200 – 1400 CE

(Eastern) Byzantine Art: 395 – 1453 CE

Detail of Casket with troubadours, 1180 CE, France (source)

early medieval art (western)

400-1000 CE

The fall of Rome was completed in 476 CE when the German chieftain Odoacer deposed the last Roman emperor of the West, Romulus Augustulus.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire and without a strong central government to maintain order, chaos, and poverty ensued. Roman roads and water distribution systems decayed, farming and mining all but ceased entirely, travel was dangerous and trade routes were unused. Birth rates dropped, and disease and infections decimated undernourished human and animal populations. Western art and culture were virtually non-existent except for what was protected by Christian monks and missionaries.

In the late 700s Charlemagne, became the leader of the largest tribe in Europe, the Franks, controlling vast lands in what is now Germany, France, Austria, Hungary, and the Netherlands. He and his family engaged in decades of military incursions and conquests to acquire territory and establish a strong central government that united most of Western Europe for the first time since the fall of the Roman Empire.

In 800 A.D. Pope Leo, seeing an opportunity to reinstate a Western Church, made Charlemagne Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Although Charlemagne was unable to read and write himself, he valued culture and began a series of efforts to foster it. Monk scribes and lay craftsmen were imported into the West from the Eastern Roman Empire and began to revive Roman realism, combined with the contemporary stylisation of their eastern influence.

The Catholic Church and wealthy oligarchs commissioned projects for specific social and religious rituals. Many of the oldest examples of Christian art survive in the Roman catacombs or burial crypts beneath the city. Artists were commissioned for works featuring Biblical tales and classical themes for churches, while interiors were elaborately decorated with Roman mosaics, ornate paintings, and marble incrustations.

Ivory Panel with Saint Peter, Frankish, 6th–8th century (source)

Byzantine Period (eastern)

395–1453 CE

By the third century, the Roman Empire had become too large to be ruled by one emperor and was divided by Emperor Diocletian, into a tetrarchy and then dissolved into an Eastern and Western Roman Empire.

In 324, the ancient city of Byzantium was renamed “New Rome” and declared the new capital of the Roman Empire by Emperor Constantine the Great who adopted a protective and tolerant attitude towards Christianity, allowing Christian religious art to visibly flourish.

With the capital of the Roman Empire transferred to Byzantium (a heavily eastern colony) western art became fused with an eastern style that was symbolic and semi-abstract, typifying Egyptian and Syrian art.

Despite the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, The Eastern (being richer and stronger) continued as the Byzantine Empire through the European Middle Ages.

The general characteristics of Byzantine art saw a shift away from the naturalism of the Greco-Roman Classical tradition toward the more abstract and universal, two-dimensional depictions, with a predominance of works having a religious theme. Byzantine artists used vibrant stones, gold mosaics, vibrant wall paintings, intricately carved ivory, and other precious metals to beautify everything from buildings to books. The greatest and most enduring contribution of the Byzantine Period are the icons that are still used to adorn Christian churches all over the world.

Just as the Byzantine Empire influenced the west, intrusions by various western territories over the decades introduced their own artistic influences. The Byzantine art era was an incredibly important period of artistic development and influenced the development of early Western art history.

Fragment of a Floor Mosaic, Personification of Ktisis, Byzantine, 500–550 CE, with modern restoration (source)

Romanesque Art (western)

1000-1200 CE

Romanesque art developed around 1000 and was replaced by the rise of Gothic art in the 12th century. The Romanesque style was founded in France, but spread to Christian Spain, England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, and elsewhere to become the first medieval style (with regional differences) found all over Europe.

Romanesque sculpture and painting became vigorous, expressive, and inventive in terms of iconography – the subjects chosen and their treatment. Royalty and the higher clergy would commission life-size effigies for tomb monuments and most churches were extensively frescoed.

Classic Romanesque artwork included massive paintings on walls and domed ceilings, stained glass pieces, illuminated manuscripts, engravings on buildings and columns, and sculptures (originally colourfully painted). The art produced during this period demonstrated the growing wealth of European cities and the power of Catholic monasteries.

Arch with Beasts, France ca. 1150–75 CE (source)

Gothic Art (western)

1200-1400 CE

The Gothic art period, which started to emerge in the 12th century, was the final phase of Medieval art. Romanesque art gave way to Gothic art during the reconstruction of the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis in France. As it gained popularity and expanded throughout Europe, Romanesque art was eventually completely replaced.

The Renaissance period that followed Medieval art, generally dismissed this previous period as a “barbarous” product of the “Dark Ages” with the term “Gothic” invented as a deliberately pejorative one. First used by the painter Raphael in a letter of 1519, “Gothic” characterised all that had come between the demise of Classical art and its supposed “rebirth” in the Renaissance. The term was subsequently adopted and popularised in the mid-16th century by the Florentine artist and historian, Giorgio Vasari.

Despite its later reputation, the Gothic period coincided with an increased emphasis on the Virgin Mary and it was here that the Virgin and Child became a hallmark of Catholic art. The end of the period includes new media such as prints; along with small panel paintings frequently used for the emotive andachtsbilder (“devotional images”) a medium influenced by new religious trends – worshippers who would meditate on the Virgin or Christ’s sufferings.

Gothic painting had already made great progress in the naturalistic depiction of distance and volume and late Gothic sculpture was increasingly naturalistic. The use of shadows and light in artwork increased, and artists started experimenting with diverse and novel subject matter.

When the Black Plague struck in 1348-1350, much of what had been gained was in danger of being forever lost again when one-third of Europe’s population died. However, wealth became more consolidated in the hands of fewer families, and after recovery from the ravages of the disease, there was a return to patronage of the arts—ultimately sewing the seeds for the coming Renaissance. The trauma of the Black Death in the mid-14th century was also at least partly responsible for the popularity of themes such as the Dance of Death and Memento mori (Latin for ‘remember that you [have to] die’) .

The central panel of the artist Duccio di Buoninsegna Maestà altarpiece for Siena Cathedral 1308 CE (source)

PAINTING

Religion eventually evolved into a recurring motif in most of the artworks created during the Medieval era. Early in the Medieval era, vivid paintings with well-known saints, like Jesus and the Virgin Mary, were widespread. The Last Supper by Giotto di Bondone, painted in 1306, is one of the most famous religious works produced at this time. The apostles of Jesus are featured in this artwork, which afterward became the most frequently represented religious scenario in art history. When the Gothic art movement arrived, paintings started to include more mythology, animals, and other topics that deviated from the usual.

The Temptation of Christ on the Mountain, Duccio di Buoninsegna, Italy, ca. 1255–ca. 1319 (source)

I hope you’ve enjoyed this journey into Medieval Art!

Aquamanile in the Form of a Crowned Centaur Fighting a Dragon, German, 1200–1225 CE (source)

–

Want to see what else I do? Come peek over on my insta or grab a freebie when you sign up to my newsletter below 🙂 🙂